|

Welcome

Legacy & Stewardship

Our Puppies

Our Sires & Dams

Education: Books, Videos & Herding Clinics

What new at Las

Rocosa?

History

Las Rocosa Gallery

All About

Aussies Blog

Site Directory

Contact Us |

|

When Ernie Hartnagle came home from World War II in

1946, having served two and a half years in the Seventh Pacific Fleet and participated in

the liberation of the Philippines, there was no time to

relax or recuperate or bask in the plaudits of his

nation. Though just 20 years old, he was, like many

other young veterans, seasoned by his experiences. And

that was a good thing, because his father died while

Ernie was away in the Navy, and being the oldest child,

it fell upon him to assume the mantle of the Hartnagle

family upon his return.

That responsibility included running the family’s

99-acre ranch in Boulder, purchased by Ernie’s parents

in 1929, the year of the stock market crash, and held on

to with hard work and gritted teeth through some lean

and difficult times, and providing for his mother, two

brothers, and a sister. He quickly found that the

ranch’s yield alone wasn’t enough and began to travel

each spring to his Uncle Frank’s Bar-K Ranch in the Gore

Range, on land that is today Vail Ski Resort.

|

OL’ BLUE EYES, Foddy, a male red merle

Australian Shepherds,

on the Hartnagle Ranch

|

|

More than 50 years ago, Ernie and his

dogs

shepherded cattle in the Vail Valley.

|

There, he and Frank would fatten the herd of cattle by

driving them from one mountain meadow to another,

chasing the lush, seasonal grasses of the Rocky

Mountains. Once summer began to set in, the herd would

be based in the high country, at 11,500 feet, but for a

period in early May, some of the best grass was found in

the pastures in the valley at 8,100 feet. So every

morning before dawn, Frank and Ernie would round up the

cattle with the help of their stock dogs and drive them

3,400 vertical feet down the hill for a few hours of

grazing.

But temperatures rise quickly at that time of year, and

if the men and dogs couldn’t get the cows moving back up

the steep slopes, which are now blue and black diamond

ski runs, to the cooler fields atop the mountains, the

cows would grow obstinate and ultimately so troublesome

that even the dogs would wither. All of the dogs, that

is, except for one.

A couple of Uncle Frank’s dogs were border collies

imported from Nottingham, England. The border collie is

the world’s unrivalled champion of sheep herding, a breed

honed for this specific purpose over hundreds, and

perhaps thousands, of years. But border collies were

then newer to working with cattle and were certainly not

accustomed to covering thousands of feet of elevation

gain, at high altitudes and in wildly divergent

temperatures, over the course of a single work day. |

When the day grew too hot, and the climbs too taxing,1

these collies, famous for their drive and endurance, would fade and

quit just like the cows, while a single black, bobtailed dog named

Rover seemed inexhaustible. No matter the temperature, or the

elevation, Rover would race uphill and downhill, nipping and barking

at the cows until they resumed their march. The only way to get him

to stop working was to force him to do so, and Ernie believed that,

if not for human intervention, Rover might work himself to death.

Rover was the finest dog Ernie Hartnagle had ever seen, and he

resolved to get himself a bobtail or two for his own ranch, once he

had the money and could locate the source. At the time, he had no

idea where to get one,2

or how far this special kind of dog, which he’d gotten to know on

the slopes of the high Rockies, would take him.

|

At least in the national consciousness, Colorado is a

state with two reputations. There is its historic,

pioneering side, which conjures visions of wide-open

space and libertarian freedoms and cowboys on horseback

ranching sheep and cattle. And there is its modern-day

connotation, of ski slopes and national parks and

progressive idealism, where healthy, attractive men and

women in microfiber garments jog and bike trails and

appreciate the state’s natural beauty in more

recreational fashion. And there, connecting these two

worlds, is the Australian shepherd.

The Aussie, America’s 26th most popular breed, isn’t

Colorado’s official state dog, but it really should be.3

Considered a midsize dog of prodigious energy and high

intelligence, its general appearance, according to the

official American Kennel Club (AKC) breed standard, “is

well-balanced, slightly longer than tall, of medium size

and bone, with coloring that offers variety and

individuality.” Unlike the standards for many of the

fussier breeds, which focus largely on physical

characteristics, the Aussie’s official definition is as

much about its personality and agility: “He is

attentive and animated, lithe and agile, solid and

muscular without cloddiness.”

“The Aussie was selected specifically as a generalist,”4

says Carol Ann Hartnagle, Ernie’s youngest daughter, and

she would know. No family has held more sway over this

breed than the Hartnagles of Colorado. The primary

reason the Australian shepherd has become both the

world’s best herding and adventure dog—as well as an

excellent companion and a capable guardian—is that the

Hartnagle family, and the handful of others who helped

shape the breed over the past 75 or so years, embraced

its intelligence, drive, and adaptability to create a

dog that can and will do just about anything. “The

Australian shepherd’s hallmark is its versatility,”

Carol Ann, who’s 48, explains. “These dogs just have a

high desire to please.”

It’s hard to imagine now, but for nearly 70 years the

Hartnagles owned and grazed flocks of sheep inside

Boulder’s current city limits. A blue heron rookery was

just east of the ranch, and both Boulder and Dry creeks

passed through the property. It was in large part on

this land, which was also home to a 53-acre reservoir

(known today as Hartnagle Lake), that the little blue

bobtailed sheepdogs of the American West -- defined, in

look and character, by Rover, and others like him—became

the breed we now know as the Australian shepherd.

There were dogs that looked and acted very much like

today’s Aussies a long time before Rover, and certainly

before the dogs bred by the Hartnagles. But you won’t

find much unanimity in the Aussie community over the

breed’s precise origins before the 1940s, at least in

the distant sense. Everyone agrees that the dogs are

not actually, despite their name, a product of

Australia, but beyond that there’s little agreement.

What is likely is that the breed as we know it arose

semi-organically on sheep ranches in the middle and far

West of the United States over a period of many years

starting in the mid-1800s.

The best guess of what happened with the Aussie is that

a variety of shepherd dogs were working in the western

United States -- Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, and

California in particular -- interbreeding with whatever

other herding dogs happened to be working nearby. The

gene pool further diversified when dogs from Europe

began to arrive in the late-19th century, along with

reinforcement flocks meant to replace sheep that had

originally arrived with the Spanish conquistadors, but

which became lunch during the California gold rush and

Civil War. These dogs accompanied sheep that may have

been imported from Australia -- which is one good guess

as to how the name arose. Other shepherd dogs that

existed in the West originated specifically in Spain --

these were larger dogs -- and so the argument can be

made that Australian shepherds are largely Spanish, and

specifically Basque.5

The reality is that it’s impossible to reconstruct an

exact history of the Aussie. It’s not uncommon for dog

breeds to lack a succinct, annotated history. Although

many were very specifically engineered from a traceable

set of forebears,6

others -- like the Aussie -- just sort of happened by

circumstance. The Australian shepherd isn’t Australian,

or English, or Spanish. It’s all of the above. Though

the best answer of all is that it’s American, with the

West, and Colorado in particular, at its core.

By the mid-20th century,

around the time Ernie was first smitten by Rover, it had

finally occurred to people to start writing things down,

and the story of the Australian shepherd began to

crystallize. Before that, dogs that appeared to be

Aussies were doing their jobs all over the West, but no

one seemed interested in documenting their provenance.

It didn’t matter to most owners where a particular dog

came from, or who its sire was; it only mattered that

the dog was good at its job. Very often you will find

these dogs referred to in old texts as “little blue

dogs” or “little blue bobtails” or, especially among

natives in Colorado, “ghost-eye dogs,” and it’s pretty

clear that the three common physical characteristics of

the Australian shepherd, as it developed organically,

were a blue coat, a bobbed tail, and a high occurrence

of blue eyes. |

DOG DAYS:

Ernie and Elaine

Francis, a male Aussie, on the ranch

Three Aussie pups |

|

FAMILY TRADITION:

Carol Ann and Jimmy

Hartnagle family award and

memorabilia

collection

Ernie’s Dorset sheep

|

The characteristic that led to these dogs becoming a

formal breed, however, was the thing that struck Ernie:

their ability to “work” livestock -- at first sheep, but

also horses, cows, ducks, geese, or any other animal a

farmer might need to tend to.7 And because of

their remarkable abilities, bobtails began to show up in

and around Colorado.

Rover was the dog that first caught Ernie Hartnagle’s

eye, but it was a pair of dogs he encountered at a local

stock show in 1952 that forever changed the course of

his family’s history. There, Ernie met Jay Sisler, a

rodeo star whose act starred Stub and Shorty, a pair of

blue bobtails who performed dozens of remarkable tricks

and became so beloved and famous while part of a touring

show that they went on to star alongside Slim Pickens in

a 1956 Disney television show titled Cow Dog.

Ernie couldn’t believe what he’d just witnessed at the

show -- dogs walking for minutes on end on hind legs, or

doing handstands atop broomsticks, and any number of

other impressive, intricate tricks on command -- and

after the performance he sought out Sisler, who told him

that these off-the-chart smart dogs, which looked and

acted like Rover and the other bobtails he’d seen

working sheep, were known as Australian shepherds.

“We’d never heard that name before,” Ernie recalls,

“but we decided then we’d get some of those dogs.”

One year later, in 1953, Ernie met and fell in love with an A&W Root

Beer stand carhop named Elaine Gibson, who just happened to have

grown up amongst these dogs herself. Elaine knew them as “bobtailed

shepherds,” and the Gibsons of Wyoming had owned them as far back as

the 1920s, when her grandfather had one he called Bob (for its tail)

that he used to bring his colts in from the range to prevent them

from being attacked by mountain lions. It’s a funny coincidence,

Carol Ann says, “that both of my parents have a very unique history

in parallel with these dogs.”

The Hartnagles acquired their first bobtail together the same year

they met, a female named Snipper, and very quickly sought to add a

second dog like her to the family. In 1955, when Ernie spotted an

ad in the Denver Post for “blue Australian shepherds” at an address

outside Littleton, he drove down and met Juanita Ely, a “salty ranch

woman from Idaho,” as Ernie describes her. Ely got her blue dogs

from Basque shepherds, and the animals looked a lot like Rover and

Snipper. Ernie and Elaine were thrilled; they’d found their source.

The Hartnagles took home their second Aussie, Badger, and were so

taken with his herding ability and courageousness that they went

back to Ely again for Goodie, Badger’s half-sister. Those two dogs

became the foundation of the breeding program for all the family

dogs that would follow.

It was Ely, Ernie says, who is probably most responsible for the

Aussie getting its start. Though Ely’s goal was never to open the

pipeline, by breeding high-quality blue, bobtailed sheepdogs of

Basque origin, Ernie says, “She was the fountainhead.”

Back home in Boulder,

Ernie and Elaine began to mate one good bobtail to another with the

sole criterion in selection being the dog’s aptitude to work, and

the Australian shepherd as we know it today began to take shape.

The idea, at the time, wasn’t to build a kennel. “We just liked

the dogs. And we liked what we had,” Ernie says. “But I got to

thinking, ‘Boy, everybody with livestock should have one of these

dogs.’”

The Hartnagles started by breeding dogs for themselves

in 1955, but word of the Hartnagles’ dogs soon spread

across Colorado, and then across the entire western

United States: If you needed a good cow or sheep dog,

you went to Boulder to see the Hartnagles. Las Rocosa8

Kennel was christened in 1970, and by then the

Hartnagles were averaging about eight litters a year.

Today there are four recognized colors for purebred

Aussies: the blue merle, the red merle, the red tri, and

the black tri, and among the landmark accomplishments to

originate at Las Rocosa was the introduction of the red-colored

Aussie (in 1970) and the recognition that black dogs, in

addition to reds, were just as capable as the legendary

blues. “We lifted the black dog out of the cheap

seats,” Ernie says. “We said we believed that color

doesn’t make any difference. You may like one better,

but the black dogs are just as good as the blue dogs.”

To make that statement as clearly as possible, the

Hartnagles set a single price for their puppies,

regardless of color. This wasn’t just unprecedented; it

was revolutionary. Years ago, before the Hartnagles

vouched for the quality of red and black Aussies,

ranchers often killed the puppies to save themselves

from having to raise a dog that couldn’t work. As Ernie

explains it now: “People did not understand breeding

these dogs.”

|

|

Very quickly, red came into vogue, and the Hartnagles figured out

that, because the color was a recessive trait, the only way to

produce red out of non-red dogs was if both parents had the gene in

their backgrounds. Today, breeders can learn the genetic makeup of

their dogs through simple DNA tests, but back then, Ernie says, “It

was just a step-by-step process. The only way you learned something

is you made a mistake.” And when you did, “you made a rule so you

wouldn’t make that mistake again.”

The Hartnagles weren’t alone. Colorado became the hub of Aussie

activity, mostly because it was a center for American livestock.

(The National Western Stock Show was an unofficial gathering for

Aussie breeders and enthusiasts.) Las Rocosa -- which, in 1991,

would become the first kennel awarded Hall of Fame status by the

Australian Shepherd Club of America and later became the first to be

given Hall of Fame Excellence status -- provided many of the

foundation dogs you’ll find in the Aussies of today.9

The Hartnagles weren’t the only ones pursuing the perfect Aussie.

Ernie says that pretty much every Aussie in America has its origins

in five basic foundation lines, and all but one of those lines comes

from a Colorado breeder. First and foremost, obviously, is Las

Rocosa, with the other key players being Juanita Ely, Fletcher Wood,

and Dr. Weldon Heard. Whereas Ernie Hartnagle was in pursuit of the

ideal herding dog, Heard, through his Flintridge kennel, was chasing

a different sort of perfection and was focused more on structure and

appearance, which translated well into the conformation ring.10

Specifically, Heard studied and followed the strategy of old German

Weimaraner breeders, who would allow only the top two puppies from

each litter to reproduce.

Heard’s impact on aesthetics was especially huge. “Of all the

foundation bloodlines,” the Hartnagles write in The Total Australian

Shepherd, “the Flintridge line exhibited the greatest influence on

the modern show Australian shepherd.” Heard died in 2008, and by

that time had stopped breeding dogs. Likewise, the lines of Juanita

Ely, Fletcher Wood, and Jay Sisler have also long since ceased. Of

the five foundation lines of the Australian shepherd, only Las

Rocosa is still active, through the work of Ernie’s two

Colorado-based children, Carol Ann and Jimmy.

|

Jimmy in the dog training pen

on the

ranch |

|

Ernie with Brombie near the

ranch house |

By the 1990s, the city

of Boulder had grown so rapidly that it basically encircled the

Hartnagle family ranch. In 1997, Ernie and his family sold it to

the city, and it became “open space.” Now, pretty much every day of

the year Boulder residents jog and hike on this land, often with

Australian shepherds at their sides. Bisected by Boulder Creek, and

with sweeping views of the Flatirons, it is some of the most

pristine land remaining in the city.

Ernie and Elaine relocated to a smaller, 78-acre ranch

near the town of Kiowa, about an hour southeast of

Denver, where, in addition to a couple of horses and a

donkey named Lila Jane, the couple keeps a pair of

Aussies that assist Ernie in his daily chores. Among

their jobs: fending off coyotes, rounding up Ernie’s

flock of purebred Dorset sheep11, and separating specific

animals when it comes time for vaccinations. Ernie,

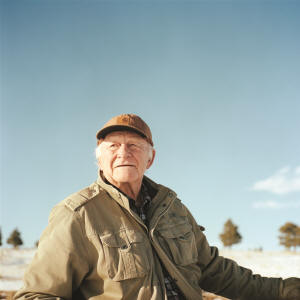

tall, broad, and ruggedly handsome, even in the second

half of his 80’s, still shears the wool and on occasion

ventures out to judge some of the Australian shepherd

herding competitions.

Carol Ann (and her husband, Kenneth Madsen) and Jimmy

(and his wife, Lisa) are now the primary torchbearers

for the Las Rocosa brand. Carol Ann and Kenneth own

nine Australian shepherds ranging in age from three to

15, and the couple still breeds, but no more than one

litter a year from their small Adams County farm. She

says she can’t remember any part of her life that didn’t

prominently feature Aussies. The dogs worked with her

siblings in the pastures, and the family traveled to

herding competitions12

on weekends. “I’ve known nothing else than having these

dogs as part of our lives as companions and guardians

and partners on the ranch,” she told me. |

By the time Carol Ann was born, in 1963, Las Rocosa was so abuzz

with Aussies that “the dogs almost raised me,” she says, and she’s

only exaggerating slightly. One of her earliest memories on the

farm, she recalls, is of a dog named Daisy who was entrusted with

the very important task of keeping the toddlers away from the long

driveway that led to the busy road out front. Daisy was taught to

give the kids a certain amount of leeway, but if they reached a

certain point, “she would interrupt us and dissuade our path,” Carol

Ann says. “She would gently take our hands in her mouth. Her task

was to keep us safe. It was amazing.”

Carol Ann says one of the things she’s most proud of is that --

despite the fact that official AKC recognition in 1983 caused a

spike in popularity that continues to this day, and the fact that

the dogs have found a second niche as the go-to breed for the

hiking/biking/skiing adventurer -- the Australian shepherd is still

primarily doing what it was bred for. “A significant number are

still raised for real-world conditions,” she says, meaning for

working on ranches, with sheep and cows. “Not too many breeds in

America that can claim that.”13

|

Working for a living - One of the

Hartnagles’ Australian Shepherds, Brombie,

moves Dorset

sheep to the ranch’s dog-training pen. |

AMERICAN ORIGINAL:

Ernie Hartnagle on his ranch in Kiowa. |

Though she has a busy career as an executive for a professional

records management company, Carol Ann, like her sister Jeanne Joy,

the author of All About Aussies: The

Australian Shepherd from A to Z, still travels widely --

even sometimes overseas -- to judge Australian shepherd conformation

and stock trials. One reason she breeds so few litters is that she

insists on being present for the births and for the early weeks when

the dogs’ personalities begin to develop.

The last time we spoke, in early December, she had a litter of

puppies that was just 14 days old. It was a breeding she’d been

planning for four years, and when the pups arrived, it was a

profound occasion. Both the sire and the dam have lineages that go

back to the very first dogs that Ernie and Elaine used to start the

Las Rocosa line. These puppies, Carol Ann said, “are the 16th

generation of our family program.”

Ernie might no longer have much of a hand in the operation, but Las

Rocosa’s impact lives on. “I would say definitely that the breed is

synonymous with our family,” Carol Ann says. “Anybody who has

knowledge of the breed would understand that, and conversely no one

can know anyone in our family without knowing the synergistic

connection to Australian shepherds. They’re one and the same.”

Footnotes:

1. In places,

the terrain was so steep that the men had to dismount their horses.

2. The idea

that a dog would have a specific, traceable, documented lineage was

an utterly foreign idea to Ernie, and probably most people, at the

time.

3. There are

currently just 11 U.S. states with an official state dog. The honor,

believe it or not, requires an act of the state Legislature.

4. This stands

in stark contrast to the majority of dog breeds, which were bred

with very specific purposes in mind. The dachshund was bred, for

instance, to crawl into holes and ferret out varmints, which is why

it’s so feisty and prone to tearing small objects to shreds.

Another popular ranch dog, the border collie, was refined by the

English and Scottish for hundreds of years to work with sheep. It’s

a champion of sheep herding, but it doesn’t want to do much else.

If you buy a border collie and ask it to be your house pet, prepare

for shredded carpets and herded children. That’s because, explains

Carol Ann, “a border collie’s desire to please a handler is not

greater than their desire to pursue their own instinct.”

5. In the

years after World War II, a federal government program, in

conjunction with the Western Range Association, granted three-year

visas to foreign shepherds who could help fill in for the lack of

able-bodied males in the United States. Many were Basque.

6. For

instance, the bullmastiff was created by English game wardens to

ward off poachers by mixing tenacious bulldogs with hulking

mastiffs.

7. Including

children. Aussies are famous among farmers for their ability to

pitch in with babysitting.

8. Spanish for

“the Rockies.”

9. “Foundation

dogs” is breeder jargon for the most prominent specific animals in a

pedigree. If you trace a modern Aussie’s family tree back far

enough, there’s a very good chance you’ll find some Hartnagle dogs

in there.

10. That’s a

fancy word for dog shows of the kind you see at Westminster in New

York City.

11. Numbering

38, Ernie’s flock is one of the largest in the region for this

breed.

12. These events

started, in large part, due to the efforts of Ernie and Elaine to

increase interest in the breed.

13. When was the

last time someone you knew bought a terrier, for instance, for the

primary purpose of killing rats?

Back to top of page

Josh Dean is

the author of Show Dog: The Charmed Life and Trying Times of a

Near-Perfect Purebred, which published by HarperCollins. His

writing has appeared in GQ, Outside, Men’s Journal, and the New York

Times. Email him at letters@5280.com.

|

HARTNAGLE’S LAS ROCOSA AUSSIES

E-mail:

lasrocosaaussies@aol.com

Telephone: 303.659.6597

Fax: 303.659.6552

Breeding Sound Versatile Aussies Since 1955

Founding/Lifetime Members ASCA and USASA

Copyright© 1999-2015. All

information, pictures & graphics contained on this website belong to

Las Rocosa Australian Shepherds & cannot be reproduced without

written consent. All Rights Reserved.

The Hartnagle's Las Rocosa

website designed & maintained by

Mikatura Web Design

|

|